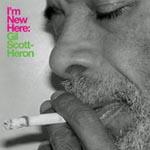

Gil Scott-Heron I'm New Here

(XL Recordings)

If Gil Scott-Heron is anything other than brilliant, he’s striking. My first exposure to Mr. Scott-Heron was through a greatest hits compilation, his song Whitey On The Moon a contained but irate dig at American expenditure and, for me, a window into that world of 1970s pre-hip-hop African American poetic dissidence. The words were great, but I was more taken with his delivery, Scott-Heron’s jazzy articulation and his angry and youthful language finding resonance with his audience, but also with anyone willing to listen.

The voice of Gil Scott-Heron signaled a creative and societal uprising, or at the very least a social consciousness within and outside of the inner city. Years later, the voices of Chuck D, Ice Cube and KRS-One would continue in such a tradition, though with living room televisions now tuned to MTV, and Run DMC’s breakthrough to suburban youth funneling this new language into the otherwise sheltered communities outside the cities.

The Revolution, at least hip-hop’s revolution, was somewhat televised.

I’m New Here, Scott-Heron’s first album since 1994’s Spirits, features him as a redemptive soul with his best years behind him and his legend established. Produced by XL Recordings co-owner, Richard Russell, I’m New Here is an unimaginatively trip-hoppy (though remarkably personal) reintroduction to Scott-Heron, who spent the better part of this past decade in prison or struggling with drug abuse. Pieced together over the last two years, the album features snippet-length comments from Scott-Heron about parents, who he is and what he has coming to him. Then, you get the man in action, either scraping blues syllables from his throat with Robert Johnson’s Me And The Devil, deeply waxing poetic about lost evenings alone (Where Did The Night Go) or offering tribute to a life “guided by women” (On Coming From A Broken Home (Parts 1 & 2)). His voice a weathered and worn device, there are facets to his personality that seem to make this album work, when otherwise its disjointed presentation would seem haphazard or pasted together. It’s also very short, clocking in at shy of thirty minutes despite its fifteen tracks.

In possible acknowledgement of the torch being passed on, hip-hop being the closest equivalent to Scott-Heron’s craft these days, the album’s bookends, On Coming From A Broken Home (Parts 1 & 2), sample Kanye West’s Flashing Lights. Scott-Heron tells the story of growing up without a male figure in his life, but having the strength of his grandmother to guide him and his mother’s sacrifices to teach him. He delivers his lines with an underlying gratitude that won’t necessarily mine a listener’s tears, but ably communicates his love and respect. He’s aware that ears will hear this, so his speech is eulogy-like: informing, but devotional.

With an urban beat propelling Robert Johnson blues, Me And The Devil finds Scott-Heron modernized for the Internet age. He sounds appropriately old, which is what makes Me And The Devil so powerful. Certainly the beats have been heard time and time again, but his emotional push is captivating and the mortality he exudes is thick enough to see. This is only confirmed by his version of Smog’s I’m New Here, where Scott-Heron manages to personalize the song with a somewhat mumbling verbalization of Bill Callahan’s words:

“No matter how far wrong you’ve gone, you can always turn around.”

As covers go, for art or life, it’s perfect.

Over electro-pulsations, Your Soul And Mine revisits Scott-Heron’s The Vulture from his album, Small Talk At 125th and Lenox. He gets soulful with Brook Benton’s I’ll Take Care Of You and nervous energy follows with Where Did The Night Go, detailing his struggle to write a letter to his anonymous “baby.” New York Is Killing Me decries the luster of city life, a clap-a-long and soul choir there to soften Scott-Heron’s caustic and bluesy throat.

Particularly engaging is Running, where Scott-Heron talks himself in circles while communicating a certain futility in “escape.” He then haunts with The Crutch, a Mezzanine-like beat adding a loud severity to the words.

Having read other reviews of this album, Gil Scott-Heron’s association with Richard Russell has been compared to the partnership between Johnny Cash and Rick Rubin that brought about the American Recordings series. It’s not an inaccurate assessment, as both artists, with the aid of producers, shed their former selves and face(d) their respective future.

In Scott-Heron’s wake, hip-hop was birthed, raised and unceremoniously twisted into a commercialized and over-polished by-product of its former self. You get a sense that inasmuch as he allows modern beats and production to drive his poetry, as a hip-hop forefather, or “godfather,” the genre only has relevance so long as he continues to thrive. (Or, so long as the genre can claim an intellect, which is difficult to find these days. At least, from a mainstream standpoint.) It almost seems as if, while Scott-Heron lost his way, so did hip-hop, a directionless child seeking and requiring guidance while its older and wiser brothers and sisters, closer in age to its progenitors, only offered judgment or comment.

With I’m New Here, Scott-Heron isn’t there to judge anyone. On the contrary, in a way, he’s seeking absolution for his mistakes, but not for his past or his present. One of the interludes, I've Been Me, says it best:

“If I hadn’t been as eccentric, as obnoxious, as arrogant, as aggressive, as introspective, as selfish, I wouldn’t be me. I wouldn’t be who I am.”