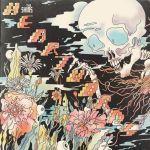

The Shins Heartworms

(Columbia)

A quiet wish for validation surrounds most of James Mercer’s musical decisions ever since he proclaimed The Shins to be a product of his own accord. He’s in every way entitled to assert that it was driven from his own artistic motives, but perhaps the way he handled it, and with such haste, immediately discredited a band who’s been ingrained in the minds of many as a truly collaborative project. From the barbarous schizo-pop of Chutes too Narrow to the beautifully textured Wincing the Night Away, it was a natural progression into well-deserved major label status. And it wasn’t in any way directly correlated to the benefit of getting immortalized as a movie reference. One could sense an air of desperation in Mercer trying to justify the role of the auteur, and if hiring a cast of professional musicians could fulfill that need then any future decision making will inevitably suffer.

To Mercer’s credit, the more classic pop-leaning Port of Morrow was certainly the logical step since it turned its back against the rest of The Shins’ input at the time. It was orderly and sometimes even frustratingly pedagogical, the musical equivalent of folding a handkerchief on your suit pocket. He was nurtured by rock classicism, as it progressed through a cumulus of backwards-looking radio friendly sounds that would once and for all prove that he was the brains of the operation. So it would only make sense that Mercer would want to disrupt things for a follow-up, even if that meant ruffling up the more prim efficiency of Morrow. In Mercer’s mind, Heartworms would resemble the more rambunctious spirit of The Shins (though it retrospect, Oh, Inverted World has more in common with Morrow if you enhance the album’s primal production framework and dainty translucence.)

In Heartworms, there’s a vague resemblance to past efforts in how it uses and manipulates a series of sonic trinkets to enhance what are essentially painterly folk songs. Rubber Ballz is a good example of how Mercer can unobtrusively adorn a simple song, where he is in shambles and trying to make sense of his questionable lays as amiable strums and castanets provide a sitcom feel to his poor choices. The cowbell-timed Name for You should also appeal to the devoted The Shins listener, a quirky and charming ode to his daughters that, like some of Wincing the Night Away, combines genuine sophistication with some slight experimental touches. There’s not much of a thematic coherence in Heartworms as it seems to only follow whatever was on Mercer’s head at the time that he wrote it. And the stream-of-consciousness thoughts that float over his head on Dead Alive, which alludes to how we distort past memories, sound apt for the song’s spooky country stride.

Most of Heartworms does follow a template that Mercer is very familiar with, and as a result, he’s able to play around with different sounds and give them more of a studio treatment. The jovial title track is another in a long track record of bottling up contradictions, where he brings up feelings of unease even when the bubbly subtext says otherwise. But all of the chances he takes don’t necessarily work to his favor: Cherry Hearts comes across as too cluttered and busy, and splicing Mercer’s weedy vocal refrain to such a disarrayed mix just gives it an unintentionally comic effect. And in an awkward attempt to sound less earnest, the awkwardly slinky Painting a Hole sounds like Mercer is trying to vie for enigmatic status in a similar style to Arcade Fire’s faux-affectations in Reflektor. Better to stick with further enhancing his more rockist tendencies, like the album’s best track Half a Million, which marries some affable glam posturing with hooky, new-wave popcraft.

For all that Mercer tries to achieve in Heartworms, and as is usually the case with most of The Shins’ catalogue, the strongest cuts are often the ones that uncover little details with emotional nuances and careful articulation. The unlikely single Mildenhall was chosen for the mere reason of attenuating Mercer’s alter ego, as it documents the music that shaped him at a young age as if he’s dusting off an old diary. But there’s also that other side of him that yields freely to his more prickly impulses, as if he hasn’t quite figured out how to recapture a time when the need to fulfill expectations was nonexistent. It’s an unusual place to be at, where you’re riding on the coattails of past success (well, pre-meme mythologizing) with an almost surgical evaluation of what constitutes a Shins record. There are so many ideas in Heartworms that give substance to Mercer’s unremitting passion to create, and though he manages to enliven and push the project forward it more so blurs Mercer’s artistic and commercial ambitions.

13 March, 2017 - 04:32 — Juan Edgardo Rodriguez